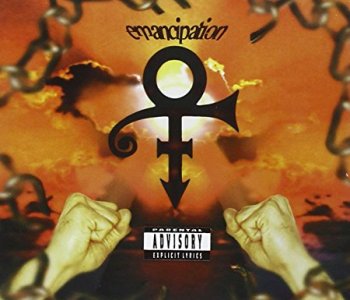

There’s a reason why being a Prince fan is a full-time job: the dude, quite frankly, recorded and released music at such an absurd clip that playing catch-up is exhausting. Consider that, for the purposes of this project, I’ve chosen to mostly focus on proper studio albums (we’ll see a couple of internet-only releases and some live stuff a little later), and I’m still at least 20 write-ups away from seeing the light of day on this thing; that’s a ridiculous rate for an artist that also locked dozens of albums away in his legendary vault, an artist with a series of bootlegged recordings entitled The Work that I’m not even planning to touch in review form, an artist who two years after Emancipation would dump a three-disc rarities set, an acoustic record, and an instrumental album onto the market at the same time. In 1996, Prince feuded some more with his record label, soundtracked Spike Lee’s Girl 6 in March (a release not covered here because it’s mostly previously-released material and WHAT AM I A MACHINE), released Chaos and Disorder in July, and then split from Warners and dropped Emancipation in November.

OH AND EMANCIPATION IS THREE DISCS LONG.

And it’s not a multiple-disc release in the vein of, say, Wilco’s Being There, a double album short enough to squeeze onto a single-disc but released as a double platter as tribute to the vinyl era. Nope, Emancipation is a full-scale flood of music, each disc totaling one hour, its runtime amounting to three total hours of music. That’s a full Lord of the Rings movie’s worth of music, although, to be fair to the artist, Emancipation is actually something I largely want to spend three hours partaking in.

It’s still a very unwieldy record, but that’s kind of by design. See, the Warners weren’t necessarily very supportive of Prince’s restless creative muse: they wanted a proper promotion and tour cycle for each individual record, while Prince just wanted to flood the market with his material, assuming (perhaps correctly) that his devotees just wanted as much music as possible to devour. They also put the kibosh on P covering other artists, and Prince valued the practice of the cover version, seeing the history of pop music as something up for grabs for him to reinvent in his own image (he didn’t have the same free-love view of other people covering his songs, but hey, if you’ve come this far on this journey with me you’ve also come to accept that Prince was kind of cuckoo-pants). Emancipation, then, is a post-Warner Brothers kiss-off, as much as Chaos and Disorder was: it finds Prince flooding the market with too much music at one clip, liberally sprinkling cover songs throughout, and basically doing everything the Warners wouldn’t allow him to. It’s the sound of Prince creating on his own terms again, basically, and if the result is messy and undigestable, it’s also one of the happiest-sounding records in his entire discography.

It’s right there from jump street, in leadoff track “Jam of the Year”, celebratory with piano trills, funk guitar, and a terrific Eric Leeds sax riff. It’s apparent that P is in full-blown r&b mode throughout disc one: “Right Back Here in My Arms” boasts a tasty g-funk bounce, “Get Yo Groove On” is disco-ready r&p, and “Somebody’s Somebody” finds Prince going full Keith Sweat for a whole cut. Prince also transforms Bonnie Raitt’s “I Can’t Make You Love Me” into a candlelit slow jam, makes detours into swing (the strangely delicious “Courtin’ Time”) and pop-rock (“Damned If I Do”, kind of addictive), and really ’96es the hell out of The Stylistics’ saccharine classic “Betcha By Golly Wow”. (“Betcha By Golly”, in particular, juices up the elevator-ready soul ballad with one of P’s most glorious falsetto performances; there’s a “thinkin’ of YOOOOOOOOOOOU” at the climax that makes me applaud every time.) The first disc rounds out with “In This Bed I Scream”, one of P’s great unsung pop songs, a guitar-and-synth laced gem that morphs into a dark NIN instrumental in its last minute.

If the first disc ramps things up, disc two downshifts: recently married at this point, Prince dwells on love-besotted ballads for the middle act of Emancipation. It’s reflective of P’s newfound romantic bliss, which is great and all, but it’s also a touch boring: “The Holy River” is wonderful, what with its waves of fervent, starkly honest sermonizing, and the shimmering “Dreamin’ of U” is an utter jewel, but the perfunctory, similar “One Kiss at a Time” and “Soul Sanctuary” bleed into one another too easily, “Emale” gives us go-nowhere funk and “Curious Child” plays like a forgotten number from a lesser Disney musical, and “Friend, Lover, Sister, Mother / Wife” closes the disc out, with an endearing but slow and interminably long ode to Mayte, his new bride. One of many things Emancipation teaches us: for the likes of Prince, marital bliss is kind of a snooze.

Disc three largely returns us to the dancefloor, “Slave”, “New World”, and “The Human Body” all offering up big, groovy funk tracks; the latter, in particular, experiments with acid-fried house and gives us a tasty P falsetto to chew on. Prince punches up a cover of “La La Means I Love You” with a Sade groove, and later drags Joan Osborne’s “One Of Us” into the arena with great solos and dubious vocals on the chorus; his “One Of Us” feels like he just decided to do it in the original key and realized too late that the hook exists in that weird grey area between his natural voice and his falsetto, and so he just kinda cheeses it. Like a lot of Emancipation, it kinda works, but it’s kinda sloppy too. The best cut of the album’s third hour, “Style”, kinda sounds like “Jam of the Year”, with an endless supply of Prince ‘tude and Leeds sax.

Look, I won’t lie: Emancipation is a lot. It’s so much music. And yet, I can’t help but feel that it’s kind of cohesive in a weird way. This isn’t 69 Love Songs, another landmark triple-album, wherein Stephin Merritt ping-pongs wildly between styles and giddily jumps genres; largely, Emancipation exists in Prince’s r&b/funk sweet spot, with the occasional stylistic (and Stylistics) detour just to stir the pot. It sags in the middle, drastically, and far from every cut is essential, and the first disc just pops in a way that the following two hours simply don’t. Think of it as a big ole sampler: Lovesexy this ain’t, where Prince never gave you the opportunity to jump around. Its finest moments, in pure Prince fashion, are resplendent; it’s almost impossible to take as a whole, but the fact that it hits as often as it does is a feat unto itself.

Grade: B-